PENGUIN RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS for ARGENTINA

Article below the Menu.

.

Bingham M (1999) Field Guide to Birds of the Falkland Islands.

.

ADOPT A PENGUIN TO HELP SUPPORT OUR WORK

.

PUBLICACIONES CIENTIFICOS EN ESPANOL:

.

Bingham M (2004) Manual de Instrucción para Monitoreo de Aves Marinas.

.

--------------------------------------------------

INTRODUCTION

Magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) are only found around southern South America, with breeding populations in Chile, Argentina and the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas). Best guess estimates put the current world population of Magellanic penguins at around 1.5 million breeding pairs, with approximately 700,000 pairs in Chile, 650,000 pairs in Argentina and 150,000 pairs in the Falklands/Malvinas (Bingham 2002, Bingham 1998, Bingham & Mejias 1999, Gandini et al. 1998).

Population studies have revealed a 90% decline in Magellanic penguin populations in the Falkland Islands since the establishment of a commercial fishing industry in 1988 (Bingham 2002), making penguin populations in Chile and Argentina even more important. In order to compare these dramatic declines in the Falklands, long-term study programmes were established at Magellanic penguin breeding colonies closest to the Falklands in Chile (1998) and Argentina (2003). Cabo Virgenes is the second largest Magellanic penguin colony in Argentina, and the closest colony in Argentina to the Falklands.

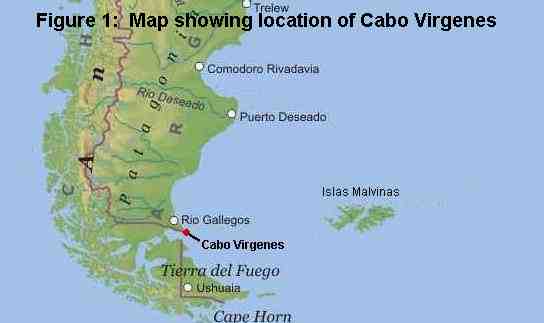

Cabo Virgenes is situated at the northern tip of the mouth of the Straits of Magellan, approximately 80 kilometres south-east of the city of Rio Gallegos (Fig. 1). Cabo Virgenes is a protected nature reserve carrying the title of Cabo Virgenes Provincial Reserve, and since 1993 it has been under the management and protection of the government agency Dirección de Fauna Silvestre y Areas Protegidas.

The penguin colony at Cabo Virgenes is protected from commercial fishing by a no-fishing zone around the colony, called the Special Protection Zone. The colony is becoming increasingly popular as a tourist destination, with visitors arriving daily in cars and minibuses. The colony is protected from excessive disturbance by tourists through the use of a tourist trail that separates tourists from the penguin nests, and by park wardens who monitor the site continuously.

In order to protect and ensure the sustainable use of the reserve as a tourist resource, Cabo Virgenes has been part of a long-term monitoring programme since 2003. This programme monitors annual changes in population, breeding success, chick and egg survival rates, and the effects of tourism, allowing the colony to be managed for the benefit of both tourists and penguins alike.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population Census

Because the Magellanic penguins at Cabo Virgenes nest hidden under dense shrubs, over an area of more than 1,00,000 sq.m., a population estimate using a direct count of all nests would be impossible. It was therefore necessary to establish long-term study plots, in which to measure population size and trends (1Bingham 2004).

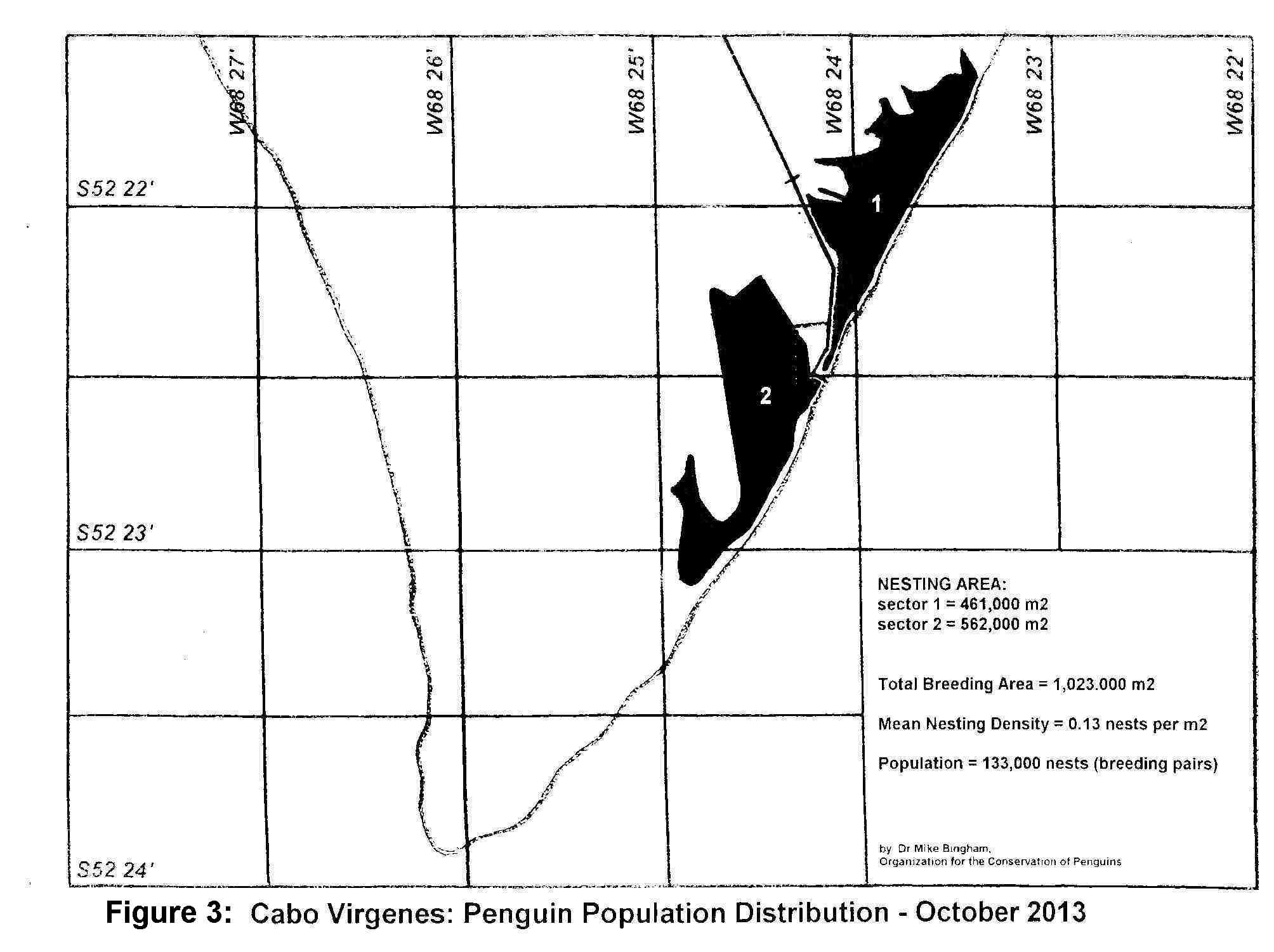

Five such plots were established in October 2003, each plot measuring 50 metres by 50 metres (Fig 2). This gives a total study area of 12,500 sq.m., which is approximately 1.2% of the total penguin breeding area at Cabo Virgenes. These plots are examined in October, immediately after the completion of egg-laying, to count the number of occupied nests, which in turn is used to determine the mean annual breeding density in nests per square metre. The nesting area of the entire colony is also mapped out using GPS, and multiplying the total breeding area of the colony in square metres, by the average number of nests per square metre recorded in the study plots, gives an estimate of the colony’s population size (Bingham 2004. Seabird Monitoring Instruction Manual for Magdalena Island. Organization for the Conservation of Penguins, 22pp.)

The greatest margin for error in determining population size using this method is in the assumption that breeding density recorded in the plots is representative of the entire colony, but by using permanent study plots year after year, this margin for error is eliminated when looking for changes in population size. Even minor changes in breeding density and total breeding area, and hence changes in population size, can be measured with great accuracy using permanent study plots, even though a greater margin of error is implied when extending this to defining an actual population size in any particular year.

Breeding and Behavioural Analysis

In addition to studying population trends, in late October, immediately after the completion of egg-laying, around 20 occupied nests in each plot are marked, and these nests are visited regularly throughout the season, to determine what proportion of eggs hatch, how many chicks survive to leave the nest, the major causes of egg and chick loss, and chick weight. Of these five study plots, plot 1 is adjacent to the tourist path where tourists walk, whilst plots 4 and 5 are in areas far away from tourists and human disturbance, allowing us to look for differences in breeding success and chick survival rates resulting from the presence of tourists. A small number of penguins choose to nest within the tourist path, despite having tourists walking around (and even over) their nests throughout the breeding season (Photo 1). These nests were also marked and studied for comparison, to see how they cope with such extreme disturbance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Penguin population census results show a population increase from 120,000 breeding pairs in 2003/04 to 133,000 breeding pairs in 2013/14 (Fig. 3).

Studies of marked nests each year support the evidence of a healthy population. Breeding success over the last 12 years (2003/04 to 2014/15) has averaged around 1.18 chicks per nest for the colony as a whole (Table 1, Figs. 4 to 15). Chick weight at the point of fledging has averaged 3.1 kilograms, indicating that chicks are well fed and healthy. Chicks with high body fat reserves have a good chance of surviving as juveniles after leaving the colony.

Analysis of annual breeding success shows that with the exception of the 2003/04 season, chick losses are low, indicating an adequate and reliable food supply during the important chick-rearing phase. The majority of the breeding failures occur during egg incubation, hatching, and whilst the chicks are small and helpless. These are mostly the result of bad weather, nest abandonment, and parents leaving eggs and small chicks to get cold. Very few chicks died once they reached 14 days of age, which is the age by which they can protect themselves from bad weather and being accidentally trampled. Above this age chick survival is mostly dependent on adequate food supply, and the very low mortality of these chicks supports the notion that food supply is generally reliable and abundant. The lack of high-intensity commercial fishing around the colony certainly plays a role (Bingham 2002).

Comparison of nests close to the tourist path, with nests in areas of no disturbance, show very little difference between the two (near to tourists = 1.10 chicks per nest / no tourists = 1.13 chicks per nest) (Table 2).

Penguins actually nesting within the tourist path itself showed a reduced breeding success (0.92 chicks per nest, compared to 1.10 chicks per nest adjacent to the tourist path). This is not surprising, considering that penguins adjacent to the path only have to cope with the stress of people walking by, whilst those penguins nesting within the path face high levels of harassment and disturbance, including people touching the penguins and their chicks. The reduction in breeding success for these nests appears to be as a result of higher nest abandonment during the egg incubation phase, with chick mortality being no higher than for the rest of the colony (Table 1).

The number of penguins nesting within the tourist path is less than 20 pairs, so these results have little bearing on the colony as a whole, but it is interesting that these penguins which face the very worst conditions possible in terms of human disturbance from tourism, still show only an 18% reduction in breeding success, and no reduction whatsoever in terms of chick survival.

It is apparent that Magellanic penguins readily adapt to the presence of tourists, and are comfortable with the current level of tourism at Cabo Virgenes.

CONCLUSION

Annual monitoring shows that the penguin population at Cabo Virgenes is healthy. Breeding success is high, egg and chick losses are low, and chicks are healthy and well fed, suggesting high juvenile survival after leaving the nest. This success is largely due to government protection offered to the colony in the form of on-site park wardens ensuring that tourists keep within the tourist path, and a no-fishing zone around the colony ensuring that the penguins’ food supply is not depleted.

Tourism appears to be having no negative effect on penguins at the present level, except for less than 20 penguins which choose to nest within the tourist path each year, which show a slight increase in nest abandonment during the egg incubation stage.

Studies in the Falklands and Chile show a link between lack of protection from commercial fishing and penguin population decline. In the Falklands, where the government refuses to protect penguins from commercial fishing, Magellanic penguin populations have declined by over 90% since the establishment of the commercial fishing industry in 1988,.and breeding success is greatly reduced each year as a result of annual chick starvation (Bingham 2002). The nearest Magellanic penguin colonies to the Falklands are Cabo Virgenes in Argentina, and Magdalena Island in Chile, both of which are protected from commercial fishing by no-fishing zones.

Magdalena Island has been studied for comparison with the Falklands since 1998, and this population is healthy and expanding, with very high chick and juvenile survival (Bingham and Herrmann 2008), whilst the Falklands colonies have declined, with mass chick starvation occurring each year (Bingham 2002). The fact that the penguin colony at Cabo Virgenes is also healthy and stable, with high chick survival, adds further evidence that protection from commercial fishing is a key factor in penguin survival. It can only be hoped that eventually the Falklands government will also begin to employ no-fishing zones around penguin colonies, in order to halt the continuing decline of their penguins.

Oil spills from passing maritime traffic through the Straits of Magellan, and from the numerous oil rigs operating in the area, are a constant threat that could seriously damage the colony at any time in the future without warning. Over the last 12 years, several minor spills have occurred around Cabo Virgenes, oiling small numbers of penguins that have been cleaned and released by park wardens. In 2009, new facilities were constructed at Cabo Virgenes to handle oiled penguins in the future, but with 270,000 penguins breeding along this small section of coastline each year, the potential for disaster is ever present.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our special thanks go to all the staff of the Dirección de Fauna Silvestre y Areas Protegidas Rio Gallegos, especialmente Marcos Clifton, Beatriz Ortega, Jorge Serra, Cesar Aminahuel, Pablo Nuñez, Carlos Raúl Oliva, Mario Beroiz, Pablo Irazoqui, Angel Mansilla, Oscar Palacios, Alberto Battini, Graciela Oyarzo, Fabián Tejerizo y Jorge Perancho. Our thanks also to the Fenton family at Estancia Monte Dinero.

LITERATURE CITED

Bingham M. (1998) Penguins of South America and the Falkland Islands. Penguin Conservation 11(1): 8-15.

Bingham M. (2002) The decline of Falkland Islands penguins in the presence of a commercial fishing industry. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 75: 805-818

Bingham M. and Mejias E. (1999) Penguins of the Magellan Region. Scientia Marina Vol:63, Supl. 1: 485-493

Bingham M and Herrmann T (2008) Penguin Research Results for Magdalena Island (Chile) 2000 - 2008. Anales Instituto Patagonia (Chile) 36(2): 19-32.

Gandini P., Frere E. and Boersma P.D. (1998) Status and conservation of Magellanic Penguins in Patagonia, Argentina. Bird Conservation International.

FIGURES, TABLES AND PHOTOS

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.